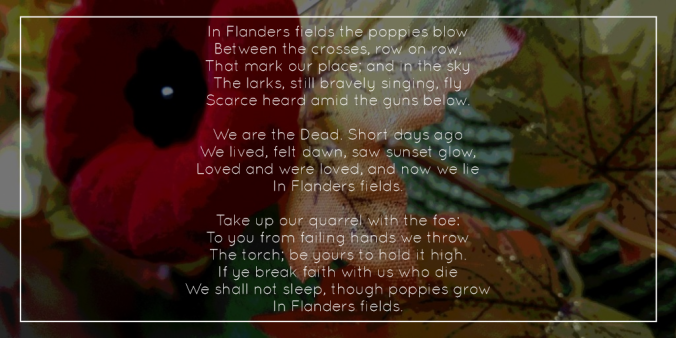

The above poem, In Flanders Fields by John McCrae is well known across Canada. The resident of Guelph, Ontario wrote it while serving during the First World War, and it was published in 1915.

Its references to the red poppies that grew over the graves of fallen soldiers resulted in the remembrance poppy becoming one of the world’s most recognized memorial symbols for soldiers who have died in conflict. The poem and poppy are prominent Remembrance Day symbols.

For the first time ever, we will be publishing here two personal memoirs, written by a Polish survivor of World War II and his older brother. These have only been edited to modify some real names and locations.

Lest we forget.

Andrzej Boczkowski

b. January 9, 1933 Poznan, Poland; d. January 27, 2014 Ontario, Canada

September 1, 1939

…Since I was only 6 1/2 when the war started, only the more traumatic experiences register more clearly. I will write about them as best as I can remember, but they will probably not be in any chronological sequence.

We lived in Warsaw in an apartment building on Sekocinska Street. It was a nice building with an arched entry to a large and treed backyard full of nicely laid out gardens. I guess we were considered an upper-middle class family because we had a maid who came in daily to cook and clean. My father was a Captain in the Polish Army and my mother was a teacher of Biology, I believe.

The first thing I remember was my mother crying while saying goodbye to my father who was being sent to the Eastern Front to join his unit. That was probably two weeks before the war started on September 1st, 1939.

Here is a bit of history I got from the internet. In August of 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression agreement, which in effect stated that if one country went to war, the other would not interfere. They also signed a supposedly secret agreement that when Germany invaded Poland, the Russians would invade Poland from the East but stop at a predetermined point. This agreement was no secret to Poland that’s why our father was sent to the Eastern Front. Russia in fact invaded Poland on September 11, 1939.

My first memory of the war itself is standing outside of our apartment building and watching fascinated a lot of aeroplanes in the sky – until the bombs started falling. We scrambled back to our building and huddled in the basement.

After the bombing stopped, I remember going out to a nearby railway station where I saw a number of dead bodies lying about, men, women and children. They must have just gotten off the train when the bombing started. However, the thing that sticks most in my mind, is the smell of burning flesh. Across from the station, a bomb blew out the front of a building and I could see a body, its flesh still smoldering and the smell was overpowering. There must have been other bodies we could not see buried under the building.

I don’t remember how long the bombing lasted, but each time the air raid sirens sounded, we hid in the basement.

After a few days, we realized that we had not seen our maid. We were told afterwards that she had tried to come over to our place, but got caught in a bombing raid and had her head blown off by a piece of shrapnel.

Our mother was a very smart lady. She realized that we could not stay in our apartment building, which was fairly close to a large railway marshaling yard, a natural target for the German bombers, and eventually our building would be hit.

One day we took a chance, and hurried across Warsaw to the suburb of Sadyba, where our aunt lived on Okrezna Street. Her name was Jadwiga Jakucuk and she had two children, a boy named Janush and daughter named Hania, I am guessing that they were in their late teens or early 20s, judging by the only picture I have of them. Jadwiga was my father’s older sister and we called her Ciocia (Aunt) Jadzia.

We stayed there in the basement for the rest of the Siege of Warsaw which ended on September 28, 1939. We survived on whatever food was in the house but it was not enough. Since I was the smallest, I remember being asked to crawl out of the tiny basement window to gather some tomatoes and other vegetables which our aunt had growing in her garden. That was enough to sustain us until we could leave the house. When we emerged from the basement, we could see a large hole in the upper part of the house, where a shell had passed without exploding.

After the Polish Army defending Warsaw capitulated to the German overwhelming numbers and superior firepower on September 28, 1939, we went back to our apartment, which fortunately was not demolished by the bombing campaign.

On the way back I do not recall seeing any dead bodies (I guess they had been picked up by relatives or other people) but I saw several dead horses with terribly distended stomachs.

I assume we went back to trying day-to-day living as best we could.

Some time in the months to follow, the Underground Resistance was actively harassing and killing Germans and they were naturally quite nervous. The only way my brother and I could help was scaring them. We devised two ways: one was to simulate gunfire by packing match-heads into one of those old fashioned keys that had a hole in the end and a fancy head on the other end. By tying a piece of string to a nail inserted in the hole packed with match-heads, we improvised an explosive device by striking the nailhead against a wall anytime we saw German soldiers walking on the other side of the street. The resulting explosion sounded like a gunshot and made the German soldiers crouch down and draw their weapons. In the meantime we would walk nonchalantly as though we had not heard anything.

The other way was to place several match-heads on the streetcar tracks and when the streetcar passed over them, they would explode. I should explain that the first few rows of streetcars were reserved for the Germans and the front wheels of the streetcar would hit this improvised explosive first. The result was the same as with the other trick. The Germans would jump off the streetcar with their guns drawn and look for who was shooting at them. By this time we would be far away, but not too far away to get a good look and laugh.

One day our Aunt Jadzia came to our apartment in tears, saying that last night the Gestapo (German Secret Police) came to their house and took away Janush and Hania to the Gestapo Headquarters. As children, we were not told that they both were in a cell of the Polish Resistance Movement. Apparently, someone, probably under torture, told them their names and address.

We rushed down to the Gestapo Headquarters but could not get close to the building, as it was surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards.

Sometime later, somebody who was released by the Gestapo, told us that they were both tortured to reveal the names of the other members of their cell. When Janush was being led for another round of interrogation, he tried to jump the guards to get their guns, and was shot dead on the spot.

Hania, after being tortured and raped repeatedly, was afraid that she would reveal the names of the other members of their cell, and somehow hanged herself in her jail cell.

Their bodies were never returned to us or recovered, so we could never confirm these stories. They were probably buried in some mass grave to cover up the signs of torture.

As you can imagine, Aunt Jadzia was totally devastated, yet proud that her children, our cousins, died for their country.

My brother told me that if he ever got the title to the house in Sadyba, where our cousins grew up, he would sell the property and establish scholarship in honour of their names, Janush and Hania Jakucuk.

Even though we were under Nazi occupation, we still went to school, with the curriculum established by the Germans, which forbade certain books, such as Polish history. Since our mother was one of the teachers, she provided all the children with the forbidden books anyway. We had student guards stationed in the school corridors who would warn us if they saw German inspectors approach. W would hide these books under our clothes and put any approved books before us on the desks.

Our mother was a very inventive person. She did not make enough money to feed and clothe two boys, so she set up an illegal still in our bathtub to make liquor, which was in great demand. I remember the bathtub full of fermenting mash, probably corn, barley, or some other grain. There were lots of rubber tubes and glass jars. Since she was a biology teacher, she knew all about fermentation. The whole apartment and hallways on our floor stunk terribly, but the Nazis, fortunately, never found out.

In June 1941, Germany broke the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union and attacked Russians without any warning. The history books will tell you that was the main reason the Germans eventually lost the war, since now they were fighting on two fronts.

When we eventually met our father in Italy, he told us the story of how he survived the war. Father knew the Russians well and he knew that if they took him prisoner as an Officer, he would be executed. Just before the Polish Army surrendered, he stripped off his Officer insignia and dressed up as an ordinary soldier. It was just as well; the Russians massacred about 6,000 to 12,000 Polish Officers, which is now called the Katyn Forest Massacre. For the longest time the Russians blamed the Germans for this, until recently they admitted it was they. For political reasons, the Russians were never tried for this atrocity.

Our father was taken prisoner and sent to a POW camp in Siberia.

After the Germans attacked Russia, all Polish POWs were released and made their way to the Middle East where they were attached to the British 8th Army and fought with them right through to Italy. As a matter of fact, the Polish contingent was instrumental in winning the Battle of Monte Cassino, where many other units were unsuccessful. Monte Cassino was a monastery located on a hilltop overlooking the main road to Rome, and the 8th Army could not proceed on to Rome as long as the Germans had their guns trained on the road.

Let’s get back to Warsaw.

During the Nazi occupation, the Polish Underground Movement was very active, disrupting them as much as they could, killing Germans by the dozen. It came to the point that the Nazis announced that for every German killed, they would execute 100 Polish men.

True to their word, they did just that.

Their method was simple. Two trucks full of soldiers would arrive at each end of a street blocking all exits. The soldiers would get out of the trucks and herd all the men they could find on the street, as well as any they could find in the buildings, until they had 100. They would line them up against the wall and spray them with machine gun fire until all were dead. They left them lying in the street and left. It was up to the Poles to gather up the dead and bury them.

Many of these blood-covered walls became shrines, with flowers and religious artifacts left by anybody passing by.

Mother was caught in a couple of these sweeps, but because she was a woman, she was spared.

The German hatred of Jews is well known. Sometime in 1942, they moved all the Jews into one part of Warsaw and blocked off all the streets with barbed wire so that nobody could get in or out. After awhile, they ran out of food and hundreds died of hunger. I recall Mother, my brother, and I went to one of the blocked off streets and threw loaves of bread and other food over the barbed wire when the Germans were not watching. All the Jews were forced to wear a yellow Star of David sewn onto the front of all their clothes.

By April 1943, things got so bad in the Ghetto, that the Jews revolted in what was called the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. They were supplied with arms and petrol bombs, called Molotov Cocktails, by the Polish Underground smuggled through the sewers, until the Germans got wise to it. They poured kerosene or gasoline into the sewers and hundreds were burned to death.

To stop the uprising, the Germans methodically set fire to the buildings in the Ghetto by bombing them.

I recall standing on our apartment balcony and watching the Ghetto burning for several nights.

The Uprising was quashed by May 16th, 1943 and any remaining Jews were shipped out to the Extermination Camps.

Again, history will tell you that the German Army started losing the war on the Eastern Front due to the overwhelming numbers of Soviet troops and the extreme cold to which the Soviets were used, but the Germans were not.

The German army started to retreat towards Poland. By August 1st, 1944, the Russian army arrived on the outskirts of Warsaw, and stopped.

In anticipation of the Soviet Army advancing into Warsaw, the Polish Underground went on a full war with the Germans (known as the Warsaw Uprising) and hundreds were killed as a consequence. It is now known that the Russians stopped advancing on purpose in order for the Germans to decimate the Underground and make it easier for them to occupy Poland.

Between August and October 1944, when the Russian army finally entered Warsaw in January 1945, the Germans methodically set fire to as many buildings as they could, essentially burning down most of the city.

The Poles never forgave the Russians for this.

However, when the Russian tanks rolled into what was left of Warsaw, the people greeted them with open arms and threw flowers at the tanks, just grateful to be rid of the Germans.

Little did they realize that they were trading a brutal occupation, for another more subtle form of occupation.

When Mother realized that there would be another fierce fight in Warsaw between the Germans and Russians, she moved us all to a small town some miles outside of Warsaw (I don’t remember the name of this town) to keep us safe.

We found an unoccupied house in this town and moved in. It was a small house set amongst tall pine trees. I don’t think it was quite finished, because I fell off a second storey terrace which had no railings, and broke my arm just below the shoulder and had to wear a cast which held my upper arm in a horizontal position supported by a wire cage. It was most uncomfortable.

There are several experiences I recall from this period. The first one is a time that my brother and I went to the railway station for some reason. While the passengers were getting off the train, a group of German soldiers were watching, and when a young man got off, the Germans told him to stop.

Instead, he ran into a field of tall grass next to the station with the Germans in pursuit firing their rifles. For awhile, we could see his head above the tall grass, and then he disappeared. I guess one of the bullets hit him. The Germans went into the field and after awhile we heard a single shot. I guess they finished him off.

About a half mile from our house amongst the pine trees, there was a road and we could see column after column of German soldiers and armour escaping the advancing Russian army. Every once in awhile, a Russian fighter plane would roar over the road and spray this column with machine gun fire.

While we were watching this, a young German soldier, no more than 20 years old, in a dusty and torn uniform, not even armed, came to our door and indicated by gestures that he was thirsty. In spite of all the horrible things the Germans had done to us, including the murder of our cousins, Mother felt sorry for him and gave him some water. She did not have to do this, as by now he was no threat to us.

Eventually, we returned to our apartment in Warsaw, which fortunately was not too badly damaged, and continued with our lives.

I guess that nothing traumatic happened until we heard from our father, because my memory is blank for this period of time.

My brother Jan wrote a lengthy account of our “Escape from Poland and Communism”, which follows:

Jan (Janek) Nicholas Boczkowski

b. January 24, 1930 Warsaw, Poland

One day soon after Christmas a letter arrived from a man unknown to us, announcing that he will come and bring a message from our father.

It was all very mysterious, but the times were such that a lot of things had to be done secretly, as one never knew, if one was not exposed to manipulations of Secret Police, and people with relations in the West were considered as possible spies.One was always very careful what one said in public, who was listening, even on the other side of the wall. Eventually the man arrived on the announced day, and we were very excited to see what he was like.

He was aged about 30, dark hair, dressed rather casually and spoke with a pronounced foreign accent, at times he had difficulty to find the right Polish words, and his knowledge of grammar was to say, inadequate.

He informed Mother, as at that time, it was felt that it was better if children knew as little as possible, in case they were to be questioned by strangers at a later date.

Mother explained to us later that we have to go to Katowice on a certain appointed day.

The man left, and when the time came, we left by train from Kepno to Katowice.We took practically no luggage, just a briefcase with some sandwiches and few bits and pieces, as if we were going just for a picnic.

We arrived at Katowice in the evening and we found the address. It was a block of flats in the centre of town. We rung the bell and were led into a modern flat. Gradually more people arrived until there were about 30 people, mostly middle aged women with children of different ages.

I was probably the oldest child, aged 14 at the time.

It was early evening in February, and we were to leave for the station in small groups at 3 am for an unknown destination.

We were to have a guide, who was going to tell us what to do and who had the necessary papers.The train left the station with this strange group of people, who did not know each other. Some women started to talk to persons sitting next to them, probably just to kill the time and to find out what the other people were thinking. This probably made them feel more comfortable on this strange journey.

We left the train in a small country station, and started to walk across fields on a rough track. It was winter, but there was very little snow on the ground, but the ground was frozen and it must have been 3-5 degrees of frost.

The guide told Mother that we were to cross the Czechoslovak frontier at a remote frontier post and that he had documents, that we were a group of relatives who were going across the frontier to attend the exhumation of relatives shot by Germans in Czechoslovakia.

As soon as we started our walk across the fields, Mother realized that some of the women had fairly large suitcases and were not able to manage to carry them for such a long distance.

Also it looked rather unconvincing, that such amount of luggage was required for one or possibly two days of stay.After a few hundred yards, they were calling out to slow down, but the guide told them that he had to keep to a timetable. My mother suggested to the women to put the suitcases in a haystack, which we were passing. It was either that or go back to the station and abandon the group.

Mother was beginning to get worried about the whole lack of organization of the group and could foresee that the whole escapade might come to an abrupt and sorry end.

She knew from her experience in Underground Movement (Resistance) in Warsaw that certain rules had to be observed, if you were doing something which might be in conflict with the Communist state. Obviously we were leaving Poland illegally and we had to be on our guard or we would get caught.

Finally our group reached what turned out to be river Olza which was the borderline between the two countries. The bridges were obviously blown up during the war and not yet rebuilt, so the river crossing was equipped with a makeshift ferry operated by ropes.

There were little wooden huts on both sides for the border guards. It was early morning, so the sleepy guard checked our papers and waved us on. Mother expected that the guide probably bribed them.

We moved on and eventually arrived on a fairly large railway station in a town, which turned out to be Cieszyn, a border town, split in half by a border agreement after the First War. This town is divided by the river Olza and on one side is Polish Cieszyn and on the other, Czech Cieszyn.

Unfortunately this part of Poland was part of a dispute between the two governments in 1938 and the population on both sides is of mixed nationalities, both by choice, intermarriage, or change of frontiers during wars.

Once our group reached the station, people were tired, children crying, so that the group attracted a lot of unwanted attention. It was Sunday 2nd February, and important Church Feast and there were very few people about at this hour. The ones that were about, were in their best Sunday clothes, which made our group stand out even more.

Some of the women were unguardedly talking to local people sitting in the station, and had to answer their questions.Mother realized that some might unwittingly give away unwanted information and make people suspicious. She shared her suspicions with a single woman sitting next to us, and decided it’s time to save ourselves from the stupidity of the rest.

We moved to the far end of the station, near some toilets, completely away from the group and pretended we had nothing to do with them.

Very soon we discovered that it was a good move, Police started to arrive at the station and question members of the group.Shortly they were surrounded and led away from the station. What we expected, had happened.

Now we had to make a quick exit, before they realized that they have not caught everyone.

We were walking the streets, pretending to be locals, but Mother could see patrols of police circulating the streets. We hid in people’s gardens behind hedges, Mother realized that we had to do something if we did not want to get caught.

She noticed that some passersby were talking Polish. She stopped one pair of people and explained the situation. It’s the only chance we had!

The young people we Polish and said they could take us into a house, where it may be safe.We went into a house and were very glad to be off the street and in the warm.

After a short time the young man came in and said that this house may not be completely safe, as one of the occupants is not very friendly towards Poles and that he will take us to a better and safer place.

By this time it began to get dark and started to snow a little bit.

Mother explained to the young man that we were to meet the guide in the marketplace, where he had transport for us to take us on our journey.

He took my mother’s arm, and as he knew the town and the local language, they were just two passersby and could observe what was happening on the streets.They noticed quite a few police patrols circulating the streets, and in the main square they noticed four U.N.R.R.A. (United Nations Refugee Relief Administration), lorries and our guide arguing with a policeman.

They waited for the policeman to go and Mother quickly spoke to the guide.

She explained the situation and arranged that we will be standing on a corner of a street, and we will jump on the lorry while it’s moving slowly up the road.We left the house and thanked our saviours for their help. Mother gave them her wedding ring, as she had no local money or other valuables. We jumped on the lorry and began our journey.

It was night, and it started to snow quite hard. To complicate matters, our lorry’s wipers packed up and the driver’s mate had to stand on the running board to shift the snow. We were driving through mountains, so the going was dangerous.

We were lying on the floor of a truck with a tent-like cover. Tarpaulins and spare tyres covered us. We had to keep our heads down as the trucks were supposed to be empty, after dropping American aid in Poland, and were in transit to German ports to get another load.

We were crossing Czechoslovakia in direction of Nuremberg. It must have been 200-250 miles and all I have seen during that time is a glimpse of Prague, what I imagined was Prague castle.

By the evening we got to the opposite frontier. It was cold and it started to snow again. More tarpaulins and spare tyres covered us again.

The guards were cold, they probably looked at the papers, and one got up to look at the back of the lorry which was dark, and they never searched it thoroughly. Nevertheless, we had a few minutes of fear, the memory of which comes back whenever I watch films and suchlike, even today.We were driven through Germany. On the way we passed through Nuremberg, where the war criminals were tried by the Allied Court. I remember the old city walls surrounding the town, but we had no time to sightsee, our journey was not finished yet.

Next day we were brought to an American Military camp, where a lot of Polish ex-Prisoners of War were employed as Temporary Guards, to enable some of the GIs to go home.

The Red Cross in the camp supplied us with some clothing from American gifts, so we had a little more luggages apart from the briefcase and what we stood in.One thing, which stuck in my mind, is the fancy food we were given, hamburgers and snowy white sliced bread, which had consistency of cotton wool. We have never seen such white bread!

First time we have seen American soldiers, all dressed up in immaculate uniforms, driving Jeeps, quite a change after seeing the drab uniforms of Russians and their Communist allies.From the American camp, we were driven another 100 miles or so, to a military camp in which the Germans kept Polish Officers during the war.

It was Bavaria.Once this camp was liberated by Americans, it became Polish Army camp, to which a lot of liberated Polish compulsory war workers, and some captured Resistance fighters were brought to recuperate.

The camp was running a proper army regime, which rather amused me, as the residents a few months before were prisoners of war, and a few months later, there was full military structure, with Generals right down to Trooper. Everyone acted very important, everyone saluting each other. There were no exceptions and we had to join the hierarchy. Mother and both of us got uniforms and were allotted to a Company and given rations in the cook-house. I was quite tall so I did not look too odd in my uniform, but my brother who was only 12, had to have his sleeves rolled up a bit and the trousers turned up. We got some funny looks, but we were very happy to be in the Free West.We got new identity papers. Mother belonged to Resistance in Warsaw and she was given the title of Communication Officer. As she had a degree and was a lecturer, she qualified as Warrant Officer and had meals in Officer’s mess. We as common soldiers had to have our meals in the barracks.

There were army couriers and contact with Polish units in Italy and we werein touch with Father. Although both Germany and Italy were defeated territories, somehow their structures were beginning to be renewed and frontiers established, which a year or so after the war did not exist.

During that time, various people dislocated by the war were moving freely through former frontiers, as everything was Allied Occupied Zone, or Russian Occupied Zone. Even this frontier was pretty fluid.

Unfortunately for us, there arose another frontier, or even two to cross to get to Italy. We needed papers and reason why we wanted to go.Bureaucracy was working again. Mother was thinking of ways of getting through another frontier. We needed Italian visas, but we had no Polish papers to identify us.

We had plans of getting on a train and hiding in the toilet while it was passing over the border. We soon abandoned that plan.Finally, Father managed to get a small truck and a couple of soldiers from his Company and some papers for us, as traveling military personnel.

We got into the truck and traveled toward Brenner Pass passing Garmish-Patrkirchen beautiful scenery, unfortunately it was still April and we got caught in a snowstorm.

The guards luckily looked frozen and too lazy to check everything, especially my brother who did not look like a soldier, although he wore a uniform.As we got over the pass the weather cleared and we could see a beautiful view of Innsbruck and later views of Italy, which was our final dream destination, which seemed thousands of miles away not so long ago.

Father met us halfway to his place of stay, in Modena. It was nearly six years since we have last seen him. He looked and felt as a complete stranger.

We had to get used to having a father again.

After we got to Italy and got used to having a father again, we traveled extensively through the country, visiting Venice, Milan, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and many other places of interest.

Eventually, we settled down in Rome and visited all the places of interest. We even had an audience with the Pope in Vatican City.

I am not sure of the date, but most of the Polish people who served in the army were shipped to England and were eventually discharged to begin civilian lives. By the time our father was discharged, he achieved a rank of full Colonel, and was given the Order of the British Empire (OBE) from Queen Elizabeth.

We lived in many places in England, but one I remember most was a huge house almost like a castle, with numerous rooms, lovely gardens, and two tennis courts. It probably belonged to some Lord or Earl who could not afford to keep it up.

I learned a lot of the English language there just by listening to the radio. My parents believed that the best way to learn the language was by total immersion. They sent me to an English school even though I could not speak a word of English. Being young, it was not long before I could first understand the language and then begin to speak it.

I remember one boy who made fun of my accent and we got into a fistfight. I don’t remember who won, but he became my best friend.

After living in several towns, we moved to a little village called Sixpenny Handley, not far from Leicester. Stonehenge is on the Leicestershire Plain, and I recall my brother and I riding our bicycles around the famous stones. There were no fences or anything special about them then.

I went to Wimbourne Public School in a town not far away from where we lived and eventually graduated from there with what was called a Matriculation Certificate.

I then went to a commercial college in Leicester, where one class was typewriting. I was the only boy in the class, with the rest being girls. I have one picture taken in a park, where I am the only boy surrounded by 14 girls. A teenager’s dream.

To help out at home, my brother and I worked weekends at the Leicester railway station as luggage porters. As soon as we loaded the baggage car, we went out on the platform and helped passengers with their luggage. I think we made more money in tips than in wages.

I immigrated to Canada in 1953 [at 20 years old], and was supposed to sponsor the rest of my family shortly after arriving in Canada. To my everlasting regret, I was never able to do so. This is probably an excuse, but when I visited the Immigration Department I was told that I had to have a certain amount of money (I don’t remember how much) saved up and that I had to guarantee that I had a place of residence where my family would live. As far as I can remember, I did not have this amount and I was living in a one bedroom flat with my cousin, Julek. Still, I should have tried harder.

I arrived in Canada, Quebec City, on May 26th, 1953, on cruise ship SS Empress of Australia, where I was accepted as an immigrant and sailed on to Montreal.

I don’t remember much of the voyage, except that we were in steerage, sharing a small cabin with an older man from Ireland. He showed me his Orange sash and told me that it was his ticket to all kinds of riches, which I, a Polack Catholic DP (Polish Displaced Person and used in a derogatory sense) and did not stand a chance.

I did not associate with him, instead sneaked up to First Class and tried to find someone my own age. I did hook up with a girl and remember sitting on the deck with my arms around her and watching the Northern Lights for the first time. It was very romantic, but now I don’t even remember her name or face.

Several years later I spotted this man somewhere, and he was shabbily dressed and drove a decrepit car, while I was driving a much better car. I felt like walking up to him and asking him how his Orange sash helped him.

However, not being a mean person, I did not.

***

The rest of the memoir is about the family Andrzej creates in Canada and unrelated to the war. His older brother Jan remains in England to this day.